Proud to Be Included with These University of Missouri Alum Authors!

Author Don Winn invited me to join him for a discussion recently. Have a watch to learn about…

Hope you enjoy!

As the stressors of 2020 continue to increase—COVID-19, distance learning, an election, and a brutal fire season—filling our children’s and our own need for a daily space of respite is vital…

It’s more important than ever for (our children) to spend a part of their day lost in the pages of a good book.

LA Parent Magazine, November 2020

I had no idea, when I wrote “Escape through Reading” for the current issue of LA Parent Magazine last month, how deeply the truth of it would resonate this past week.

As my homeroom checked in via Zoom during morning meeting last week, fires were raging nearby and the tension and anxiety my fifth graders were feeling was palpable. One student and her family had evacuated their home at dawn, and so she joined our class from a hotel. Other students’ families were packing essentials and awaiting possible evacuation orders.

Fortunately, this is a group that feels safe with one another, so they could talk about what was happening and express their feelings fairly openly.

I don’t think I ever felt so grateful for the subject I teach as I did that day. The plan that morning was to finish reading a chapter together from the John D. Fitzgerald novel The Great Brain in which Tom, the novel’s title bearer, hatches a plot to get the harsh new teacher fired by framing him as a secret drinker. Talk about a great escape.

It was a relief for all of us, I think, to disappear into small town Utah of the 1890s to find out whether Tom could pull off his outrageous caper. He always seems to show the adults what’s what, which, of course, the kids love.

Diving into the story we learned that life wasn’t necessarily easy for kids back in the 19th century either. You’d have attended a one-room schoolhouse with kids of all ages and, if you got into trouble the teacher would paddle you—right in front of everybody! And so we rooted for this audacious and brilliant ten-year old hero who never fails to entertain and astonish us.

For a brief time we were transported far from our own troubling reality and enjoyed a respite from the fires, the virus, and even the distance that separates us.

What I’ve been reminded of again and again during this season of remote learning is that shared literature has the power to bring comfort and bridge the gap. It not only provides a welcome oasis from our current difficulties, but it also makes possible a sense of connection among us, even through Zoom.

Check out the November issue of LAParent Magazine on page 12 for my article “Escape through Reading”…5 tips for creating a shared reading experience in your family that will provide a powerful buffer through these challenging days.

“Bid on once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to bring acclaimed and engaging authors on virtual visits to all the places that readers gather in your life!

Look for opportunities for facilitated discussions, readings, workshops, and demonstrations by a remarkable collection of authors to enrich your next book club, family gathering, or loved one’s classroom!”

Words Alive, a San Diego literacy nonprofit, connects children, teens, and families to the power of reading.

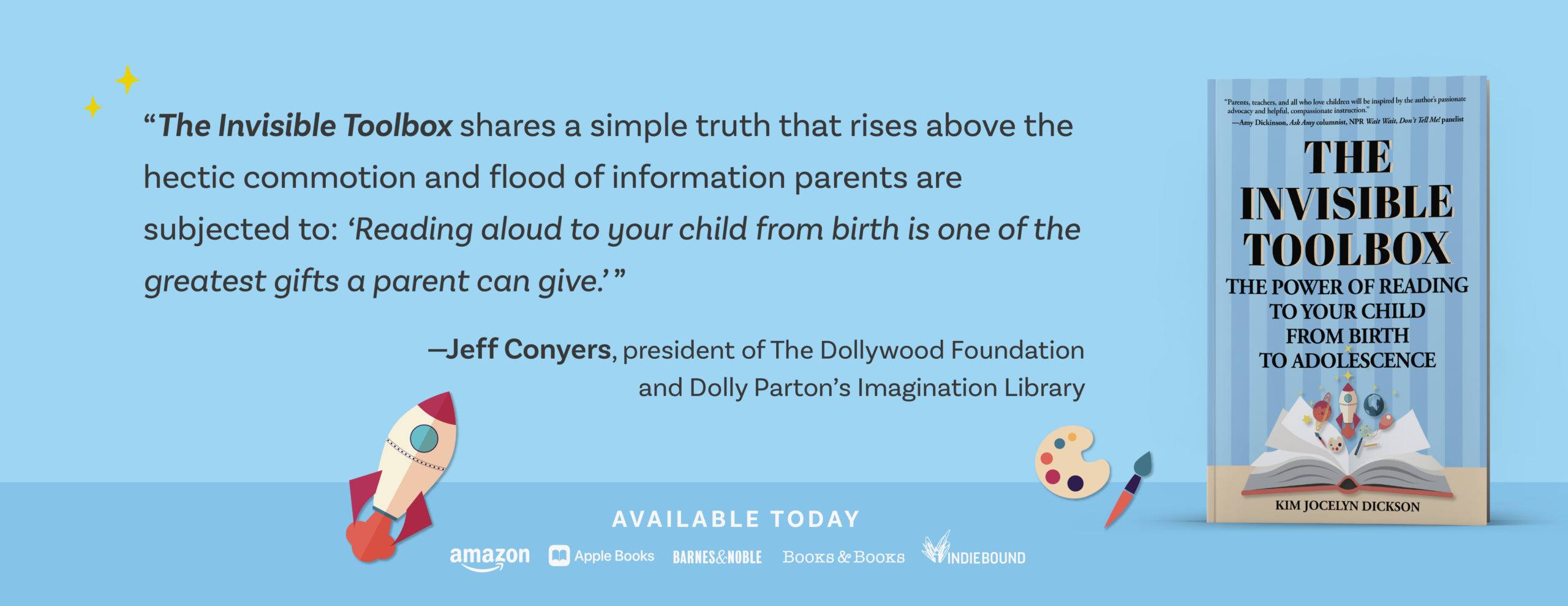

In support of their important work promoting literacy, I’m thrilled to offer a book talk on The Invisible Toolbox: The Power of Reading to Your Child from Birth to Adolescence. Find out why reading to your child is one of the greatest gifts a parent can give.

Because my talk will take place over Zoom, anyone can bid via silent auction.

Bid now and throughout the month of October and enrich your book club, classroom, or parenting group with a book talk on The Invisible Toolbox. Learn why reading to your child is one of the greatest gifts a parent can give!

Over 40 authors and their work are represented this year in Words Alive’s annual fundraiser. I have to admit I’m fangeeking out a bit to be in such awesome company. Check them all out at the link below.

http://www.wordsalive.org/authors2020

In this highly digitized climate of remote learning, reading to your child matters now more than ever. Check out this article in the September issue of L.A. Parent to find out why.

Some people become experts because they study their subjects, while others do so because of their lived experience. Don Winn comes by his expertise in dyslexia for both reasons.

I met Don when he contacted me for an interview about The Invisible Toolbox. Around this time he gifted me with a copy of his own book Raising a Child with Dyslexia. This clearly written, well researched parenting guide actually includes wonderful advice for all parents. But stories about his own struggles with dyslexia as a child piqued my curiosity as a teacher and made me want to understand more. How does someone whose needs were so painfully overlooked as a child—both emotionally and academically—manage to overcome them?

Don personifies the idea that it’s never too late to parent yourself. With the help of a few mentors along the way, he has not only faced the reality of his own learning and functioning differences, but has also become an inspiration and source of extraordinary knowledge, through his writing and speaking, for parents and children who deal with dyslexia.

In our conversation, you’ll learn about one of Don’s earliest mentors who he believes was the reason he was able to persevere through his dark days in elementary school. His grandmother who read to him filled his invisible toolbox with the understanding that reading and the wonderful closeness that comes from sharing books is worth the struggle. And so, Don Winn never gave up and gained what he believes is the superpower every dyslexic child has the potential to learn.

About Don Winn:

Don M. Winn is the award-winning children’s fiction author of the Sir Kaye the Boy Knight series of children’s chapter books and the Cardboard Box Adventures collection of thirteen picture books as well as the nonfiction book for parents and educators Raising a Child with Dyslexia: What Every Parent Needs to Know. As a dyslexia advocate and a dyslexic himself, he is fully committed to helping reluctant and struggling readers learn to love to read. Don frequently addresses parents and educators on how to maximize the value of shared reading time and how to help dyslexic and other struggling readers to learn to love to read. He’s published articles about dyslexia and reading in MD Monthly, the Costco Connection Magazine, TODAY Parenting, Fostering Families Today, and many others.

Oh, there’s so much more to it than that! Although first medically documented about 130 years ago, there are still a lot of misconceptions about dyslexia.

Dyslexia occurs when the brain develops and functions differently. It’s a neurological difficulty with decoding the written word, not an intelligence issue. The written word is a code that requires the brain to match seemingly meaningless marks on a page with the sounds we’ve heard from birth, and not all brains are structured or wired to do this effortlessly. Dyslexia is often hereditary, and rarely gets noticed until a child enters school and begins to struggle with literacy.

Experts estimate that approximately ten percent of the population is dyslexic. Most of these people never get diagnosed. Dyslexia can sometimes be difficult to diagnose because it varies so widely from person to person and can affect a broad spectrum of abilities. To complicate matters, dyslexia is actually a family of sibling conditions, and a person may experience any or all of the following conditions:

Dyscalculia: Trouble with math, numbers, sequencing, sense of direction, and time management.

Dysgraphia: Illegible handwriting or printing, incompletely written words or letters, poor planning of space when writing (running out of room on the page), strange contortions of body or hand position while writing, difficulty or inability to take notes (which requires thinking, listening, and writing simultaneously).

Dyspraxia of speech: Misspeaking words and/or halting speech. This aspect of dyslexia happens because the brain has problems planning to move the body parts (e.g., lips, jaw, tongue) needed for speech. The child knows what he or she wants to say, but his/her brain has difficulty coordinating the muscle movements necessary to say those words.

Dyspraxia: An issue that involves the whole brain, affecting movement. This can include gross (large) muscle movements and coordination as well as fine motor skills (pen grip, unclear hand dominance, trouble fastening clothes and tying shoes, difficulty writing on the line on paper). Dyspraxia can cause clumsy, accident-prone behavior due to proprioceptive challenges (ability to tell where the body is in space), trouble telling right from left, and erratic, impulsive, or distracted behavior.

All these difficulties are caused by structural brain differences that mean reading, writing, math, spelling, and more will never be automatic. A dyslexic person will never read or perform other affected tasks quickly. No matter how brilliant a dyslexic student may be, these tasks will always be laborious and will generally require extra time to complete.

First of all, I am severely dyslexic and have three of its sibling conditions—dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and dyspraxia. I went to school in the sixties, when very little was known about dyslexia or how to help dyslexic students. I felt like a normal, happy kid until I entered first grade. But on the first day of first grade, my whole world collapsed into itself, and in the space of a seven-hour school day, everything changed for me. I simply could not figure out how to do the things the teacher asked me to do.

Memorizing the alphabet, that long sequence of 26 unrelated letters, plus their sounds; reading and writing my numbers; holding a pencil the way the teacher wanted me to hold it; following instructions that had multiple steps or those that involved telling my left from my right; and so much more felt impossible even though I was trying my very hardest. My brain struggled to make sense of the fact that everyone else in my class could do these things easily. I didn’t understand why I could not. I felt like a duck out of water—I didn’t belong, and I became very anxious. It was like everyone was moving at a fast-forward speed, and I couldn’t raise my hand and say, “Stop! Slow down! I don’t get this! I can’t keep up!” Deep inside, I knew that day that there was something very wrong with the way my brain worked and things went downhill from there.

Though I didn’t have the words to describe it at the time, I now realize that neither the speed with which information was presented nor the manner in which it was taught were good matches for my processing abilities. I flunked first grade. Partway through first grade (for the second time), a special ed teacher who had taken an extension course on dyslexia recognized my symptoms and suggested that I might be dyslexic.

Once I had the label, the only thing that changed was that I now spent an hour a day with the special ed teacher to work on reading. Unbeknownst to me, my parents, or the teachers in my life, I also had dysgraphia (trouble writing), dyscalculia (trouble with math, numbers, and learning/doing things in sequence), and some dyspraxia (trouble with coordination of muscle movements needed for multiple tasks). None of those issues were ever addressed, and they caused me a lot of stress.

Over the years, the one thing that created the most difficulty for me was the lack of information leading to understanding, accepting, and coping with my dyslexia. My teachers never explained things to me, my parents never had a single discussion with me about what was going on or what we could do about it, and most importantly, there was no one I could talk to about my fears, feelings, and frustrations. About ten years ago, my wife and I made a project to understand dyslexia, learning all we could about current science, teaching methods, genetic involvement, and emotional and educational techniques that can help dyslexics cope with the fallout of their condition.

We took a huge leap forward in our quest at an early screening of the 2012 documentary The Big Picture: Rethinking Dyslexia. I had never before seen such a comprehensive and relatable depiction of all the things I had been struggling with since first grade. Viewing this documentary had a profound impact on both myself and my wife. I finally understood myself in a way I never had before, and now realized that I had a tribe. And although my wife has a background in biochemistry, psychology, and genetics, before viewing the documentary, she was completely unaware of the breadth and scope of the effects of dyslexia.

As I started to better understand my own dyslexia and the reasons why I struggled throughout my school years and early adult life, I realized that most of my struggles could have been minimized with a proper understanding of dyslexia, ongoing support, and accommodation.

Just having the label is not enough. It’s a start, but children with dyslexia and their parents need to understand what that label means in terms of life impact. And most importantly, kids need social and emotional support to be able to show up for the hard work of learning and performing academically. Warm, loving, open communication is key. A child must have hope.

Much like the show, What Not To Wear, my life is a version of “How Not To Do Dyslexia.” I don’t want any child to struggle unnecessarily like I did.

Really, the only support I ever received was from the special ed teacher in helping me to read. After that, I was basically on my own. I didn’t understand my dyslexia and I didn’t have any social and emotional support or accommodation. My parents’ divorce compounded this situation and then from 5th grade on, it seemed like I was constantly moving and starting at new schools, so my entire early education was anything but positive.

Our son got much better accommodation and help in school. The elementary school he attended was particularly good. It’s amazing what a difference a good counselor makes, and our son’s counselor took a personal interest. He would take the students who were struggling out of class when they were particularly stressed, and they all went outside and built birdhouses. It was a great way to defuse an escalating stress response, get centered, and recharge their batteries for the next educational task.

Accommodation and social and emotional support for dyslexia are just as important for an adult. Every task takes more time and that’s something that never changes. So planning my day, trying to minimize unexpected demands whenever possible, and good communication with my wife are so important. In fact, one of the most popular articles on my blog is one I co-wrote with my wife, called, “Living With an Adult With Dyslexia.” In that blog, my wife shares what she has learned about what works well for us.

Dyslexia continues to affect me with mental and even physical fatigue. I get lost easily, I struggle to keep track of things, and I face a constant demand for brain bandwidth that sometimes isn’t there when I need it for reading and writing.

Dyslexics have definite strengths, like seeing the big picture and outside-the-box thinking. They may also be very good at pattern recognition and spatial reasoning. However, every child is different and not all dyslexics have the same abilities. Some dyslexics may be gifted in special ways, but all dyslexics have the ability to develop great tenacity and grit. In fact, they have to. Because every required task demands exponentially more effort for a person with dyslexia than for a non-dyslexic, these kids learn younger than their peers that life means doing hard things. To me, this is the real superpower of dyslexia.

For example, my dyslexic grandniece wanted to enroll in a high school program that would allow her to graduate with an associate’s degree. In order to do this, she had to pass a test. It required several hours to take this test. But she really wanted to get into that program, and so she worked hard and took the test 9 times before she qualified. That’s the kind of grit I’m talking about. I’m so proud of her!

Thank you! My paternal grandmother was the only person in my family who read to me. While we didn’t get to spend time together often, when I did get to sit in her lap and share books with her, I felt safe and loved. She read slowly and asked me lots of questions to help me think about what we were reading together. I didn’t feel stupid with her like I did at other times when faced with reading. There was never any pressure, only fun. And she was actually interested in hearing what I thought! As a result of those interactions, there was a tiny place in my brain that linked reading with pleasure, and most importantly, with meaningful human connection. That little ray of hope helped sustain me as I persevered year after year with my difficult reading tasks. To this day, the time I spent with my grandmother is one of my fondest memories.

It’s not just about learning to read. Children need to feel loved and safe, and shared reading is the perfect format for creating that bond. During shared reading, a child feels loved, feels the benefits of enjoying a parent’s (or other person’s) complete attention, and feels seen and heard. An adult who chooses to spend time reading to a child says by their actions, “You matter to me. You are valuable. I want to spend time with you. I’m interested in your feelings and thoughts.” Nothing is more deeply nourishing to the soul of a young child, and a parent cannot go wrong by focusing on this important pursuit.

Thankfully, there are early warning signs that savvy parents can watch for, starting in infancy. Some tests can provide diagnostically accurate results for children as young as eighteen months of age. I provide a comprehensive list of current testing methods, broken down by age group and diagnostic focus in my book, Raising a Child with Dyslexia: What Every Parent Needs to Know.

Additionally, all my dyslexia articles I’ve blogged about are available here: https://donwinn.blog/dyslexia-articles/. Educating yourself about dyslexia and the many ways it can show up is important. Discovering ways to provide ongoing social and emotional support and accommodation will optimize your child’s potential.

My biggest recommendation to all parents: read to your child from infancy on. Start now. Start where you are. You’ll be glad you did.

My book, Raising a Child with Dyslexia: What Every Parent Needs to Know, offers a comprehensive approach to dealing with the challenges of dyslexia in the family and at school. Understanding the importance of early detection, testing, working with a child’s school, investigating possible behavioral issues, appreciating the role of social and emotional learning, recognizing the strengths of dyslexia, embracing advocacy, and much more is covered in this user-friendly guidebook. While the writing took me many months to complete, this book has been in the works for over 53 years—ever since I became aware of my own dyslexia and the needs it presents.

I’ve often wondered how my life and the lives of other dyslexics who did not receive adequate accommodation, support, and understanding would be different had we all gotten the help we needed during our most formative years. With the knowledge that’s available now, there is no reason why any child with dyslexia needs to experience this level of hardship ever again.

My website/blog is https://donwinn.com/, and you’ll find lots of information about my books and resources for teachers and parents there.

All of my children’s chapter books are available in softcover, hardcover, eBook, and audio and my picture books are available in softcover, hardcover, and eBook formats. Visit my Amazon author page for more information.

Connect with me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube

I interviewed recently with dyslexia expert Don Winn. Don is an award-winning author of picture books and Raising a Child with Dyslexia: What Every Parent Needs to Know.

Thanks so much, Don, for this opportunity! A great conversation about what really matters in the early years for EVERY child.

If you’re a parent worried about Covid-19’s long-term effects on not only your child’s academic growth, but their social-emotional well being too, you are not alone. “Covid Slide” is the new buzzphrase for the worry that students who miss out on regular school will have long-term gaps in their learning and struggle to catch up.

It’s an understandable concern. The Distance Learning programs that schools and school districts delivered during the final third of the school year varied widely. Some schools pivoted quickly into a fairly robust program, while others faltered and even petered out toward the end of the year.

Children have been out of physical school since March and, with the number of COVID cases spiking this summer, schools across the country are facing agonizing decisions about how school will take place in the fall.

The uncertainty of it all is bound to cause anxiety in parents. Sending their child back to some semblance of normalcy if their school does open under physically distanced circumstances, participating in their school’s distance learning program, or keeping them home and figuring it out for themselves are possibilities every parent will have to grapple with soon.

In the meantime, what can a parent do to help their child continue to grow academically and feel safe and healthy emotionally?

The single most important thing a parent can do during this time of school upheaval is to support their child’s love of reading. Finding pleasure in reading is so critically fundamental to all learning that fostering it is the best possible insurance a parent can employ in preventing not only academic decline, but also emotional distress.

In The Invisible Toolbox: The Power of Reading to Your Child from Birth to Adolescence, I explain the tools a parent bestows on their child through reading to them from the beginning that will affect their future school success. Here, I’ll explain just two as these are two of the most critical ones a child needs during this time.

One of the most important tools that a child who finds pleasure in reading gains is intellectual curiosity. It may sound lofty, but intellectual curiosity is simply the quality of wanting to know more about the world. Young children are innately curious, but I’ve learned through over thirty years in the classroom that this quality is easily lost if it isn’t nurtured. Children who read learn more than those who don’t, and, they are more curious than their non-reading peers.

Why is the cultivation of intellectual curiosity important during this time of interrupted school? A child who reads for pleasure during this time continues to want to know more and will read more in order to learn. They are intrinsically motivated to do this, regardless of whether they are in school or not. These students want to learn for learning’s sake. They are much less likely to fall behind and will be primed to resume regular instruction because they have not stopped learning.

Parents and all who care about children are not only concerned about academic slippage. Earlier this summer, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that schools re-open in the fall, despite spiking cases of COVID-19, for the sake of children’s social-emotional health.

Children need to be with other children, and face-to-face learning with a caring adult is ideal. But what if public health circumstances prevent this from happening in the fall? How then can a parent best support the social-emotional needs of their child?

Encouraging a love of reading is helpful here too. There are two ways a parent can promote their child’s emotional well-being through reading.

A daily family read-aloud time is a comforting oasis for both parent and child during a difficult time. Sharing a picture book or a novel together is an opportunity not only to escape into another world, but also to connect with each other through the experience. Having a parent’s full attention at some point each day has an enormously positive impact on a child’s well-being. Enjoying a story together offers an opportunity for conversations not only about the story, but also about a child’s feelings around it. This may even lead to other conversations that wouldn’t occur without the prompting of the story. A daily family read-aloud time is an excellent opportunity for bonding.

Having books to jump into independently can be a soothing haven for a child during a difficult time as well. Neuroscience has taught us much in recent years about the impact that reading for pleasure has on the brain.

What we now know that we didn’t understand before is that when we read fiction it impacts not just the language-processing portion of the brain, but all parts of the brain. Studies show that when we read, we experience the story as if it’s actually happening to us. (Murphy Paul, 2012.) What this means for a child immersed in a book is that they are truly transported when they read; they experience the story as if they are actually participating in it. Studies also indicate that reading puts our brains into a state similar to meditation and that it brings the same health benefits: deeper relaxation, inner calm, lower stress levels, and lower rates of depression.

Reading provides a healthy escape from the monotony of being stuck at home.

Lest a parent worry that their child could grow into a reading recluse unable to relate to others, studies also show that reading fiction develops a person’s capacity for empathy. Entering into a story necessitates that a reader put themselves into a character’s shoes. With fiction we come to understand that others have viewpoints different from our own. These important ingredients for social-emotional wellness cultivated through reading can make a lasting impact on a child’s ability to understand others. (Mar, 103-134)

Come fall, whether or not schools reopen, no child will experience school in the way they’ve known it in the past. Regardless of your child’s school circumstances, encouraging their love of reading remains the one of the most important things you can do.

Last spring, as soon as my school announced that we were going into Distance Learning, one of my fifth grade students made a beeline for the school library and checked out 17 books. His ability to think ahead and plan for lost access to the library was impressive. The parents of another student of mine did a very smart thing too. They ordered every single Rick Riordan title from Amazon so that their son would have a complete library of his beloved series to read during the quarantine. By June this boy had read over 19 novels.

As a teacher I felt good about the language arts program I was able to deliver remotely to my students on such short notice. It wasn’t nearly as expansive as what I would have been able to offer in person, but except for a very few, most of my students remained active and engaged until the end of the year. The boys who were reading continually for fun were two I knew I didn’t need to worry about.

Parents can let go of some of their anxiety, too, through supporting their child’s love of reading. While not every parent can afford to buy an entire library of their child’s favorite author’s books, the public library, their child’s school’s library, or free books available online can provide a child with what they need to carry them through this time of disruption and build a strong foundation for their future.

References

Dickson, Kim Jocelyn. (2020). The Invisible Toolbox: The Power of Reading to Your Child from Birth to Adolescence. Coral Gables, FL/USA: Mango Publishing Group.

Mar, Raymond. (2011). Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 62: 103-134.

Murphy Paul, Annie. (2012). Your Brain on Fiction. New York Times.

Did you know that The Invisible Toolbox is available on audio too? It’s not only a quick read, it’s a fast listen, too, at just two hours. Here’s what Adrian, the youth services librarian at the Westmont Public Library, has to say about it:

“You may have heard that it’s important to read aloud to your child from birth, but you may not have heard why…”

The Invisible Toolbox: The Power of Reading to Your Child from Birth to Adolescence is available on audio as well as paperback through these links:

Ground-breaking primatologist. Anthropologist. Conservationist. Speaker. Author.

Jane Goodall’s list of accomplishments is well known, but what may not be as widely recognized is how she came to be the remarkable woman she is today.

From early on British born Jane loved animals. In 1935, on the occasion of King George V’s silver jubilee celebrating 25 years on the throne, her father gave one year old Jane a stuffed chimpanzee in honor of the birth of Jubilee, a baby chimp born at the London Zoo the very same year.

Jane traces her early fascination with animals all the way back to her own little Jubilee who resides with her still in her childhood home in England. But it wasn’t until she was a little older that this affection expanded into a passion that would ultimately draw her into a career that changed the way the world understands animals.

As a young girl Jane grew into a voracious reader and spent hours at the public library or perched on stacks of books at her local second hand book shop. When she could save a little money, she was occasionally able to buy one. In a lovely letter to children published in A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader, Jane explains how these books inspired her future:

“…in the summer I would take my special books up in my favorite tree in the garden. My Beech Tree. Up there I read stories of faraway places. I especially loved reading about Doctor Dolittle and how he learned to talk to the animals. And I read about Tarzan and the Apes. And the more I read, the more I wanted to read.”

At the age of ten Jane decided that when she grew up she would go to Africa to live with the animals and write books about them. And that is just what she did.

Jane’s story beautifully illustrates the power books have to inspire the human imagination.

One can’t help but wonder…what if Jane had grown up in a different time? Consider the present for instance. What if she’d had access to screens and the internet and never fell in love with reading as she did? Would Jane Goodall have become the person she is today?

I wonder.

Books have a unique capacity to fire the imagination. Neurologists now know that we humans experience reading fiction as if it’s actually happening to us. All parts of the brain are engaged when we read, not just the region that processes language—which is what we used to think. The deep and organic engagement that comes with written text doesn’t happen with fiction depicted through images on a screen. A book that a child becomes immersed in, however, literally becomes a part of them.

Jane read and reread the Tarzan books, developed a crush on the noble savage himself, and was quite put out at his choice of a partner. “He married the wrong Jane.”

Fortunately for Jane and for the world, she grew up in the time that she did. She became an avid reader who found her way to the books that were right for her and, because of those books, she found her life’s passion.

What does Jane’s story have to say to us today? Simply this. As parents it is our responsibility to nourish our children’s inner worlds.

Jane was fortunate in having parents who encouraged her to believe she could do whatever she set out to do. They also supported her love of reading.With the myriad distractions parents and children face today, helping children find their way to the books that inspire them is a taller order than it was in Jane’s time. But, it is definitely doable. By reading to our children from the beginning and supporting their love of reading throughout their childhood, every child’s imagination can be sparked and ignited.

And who knows where that might lead to?